(Part one of a four-part series on early American Methodism)

During my sabbatical in 2015, I was encouraged to start reading something unrelated to ministry and picked up a copy of His Excellency by Joseph Ellis.

I finished it in less than a week.

This incredible biography of George Washington renewed in me a love for American history and soon after, I committed to reading the leading biography of every U.S. president chronologically. I recently wrapped up the New York Times Bestseller Coolidge by Amity Shlaes.

Thirty presidents down and sixteen to go!

In 2015 I also enrolled in Wesley Seminary to learn more about the history of the Wesleyan movement and gravitated to the story of early American Methodism which took root under Francis Asbury around the time of the Revolutionary War.

One of his many itinerant preachers is shown below.

That same year I attended a gathering of pastors, church planters, and network leaders designed to unleash the “mavericks” in our tribe. The gathering was designed to help spark a new apostolic movement to “reach every zip code” in America with the gospel. It also gave me an idea for an Independent Paper I wrote during my time at the seminary.

I called it Early American Methodist Mavericks.

“Some of have called early American Methodism the greatest church-planting movement in American history.”

This is no disrespect to the Baptists (who also proliferated churches during in the early 19th century) or Pentecostals (who did the same in the early 20th century) but the story of early American Methodism is incredible.

I decided to dust off my paper and will take the next four weeks (normally these articles are 2X a month) to share the fruit of my research and key characteristics of this movement.

This will not be a critique of the present state of the church or a look into future ideas and possibilities. Those ideas have been debated ad nauseam. Instead it will be a look to the past and the characteristics of the greatest church planting movement in American.

Maverick Leadership

The first characteristic of early American Methodism is Maverick Leadership!

Samuel Augustus Maverick was born on July 23, 1803 and later became a Texas lawyer, politician, land baron, and signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence. He owned over 40,000 acres of land and in 1862 became the mayor of San Antonio.

However, his most enduring legacy is his stubborn independent streak now closely associated with his famous last name.

“Mr. Maverick was also a cattle rancher who steadfastly refused to brand his own cattle.”

His stated reason for leaving his animals unbranded was that he didn’t want to inflict pain on them, but other ranchers suspected his true motivation was to collect any unbranded cattle as his own.

In 1845 Mr. Maverick acquired four-hundred head of cattle that were moved from the Gulf coast to the Conquista Ranch on the San Antonio River where they were left to multiply and graze.

In the process, his plan backfired as many of the same cattle wandered away leaving other ranchers the freedom to burn their own marks into the unbranded and unmarked “mavericks”.

The name “maverick” soon became associated with someone or something that is unbranded, and developed into one of the most enduring terms of the Old West, a word used to describe the independent-minded cowboys of old.

It is also the mascot of a great NBA team.

Go Mavs! :)

Francis Asbury

In August of 1771 at an annual conference in Bristol, England, Francis Asbury answered the call to cross the Atlantic Ocean and make the long voyage to the American colonies. There were very few workers in America.

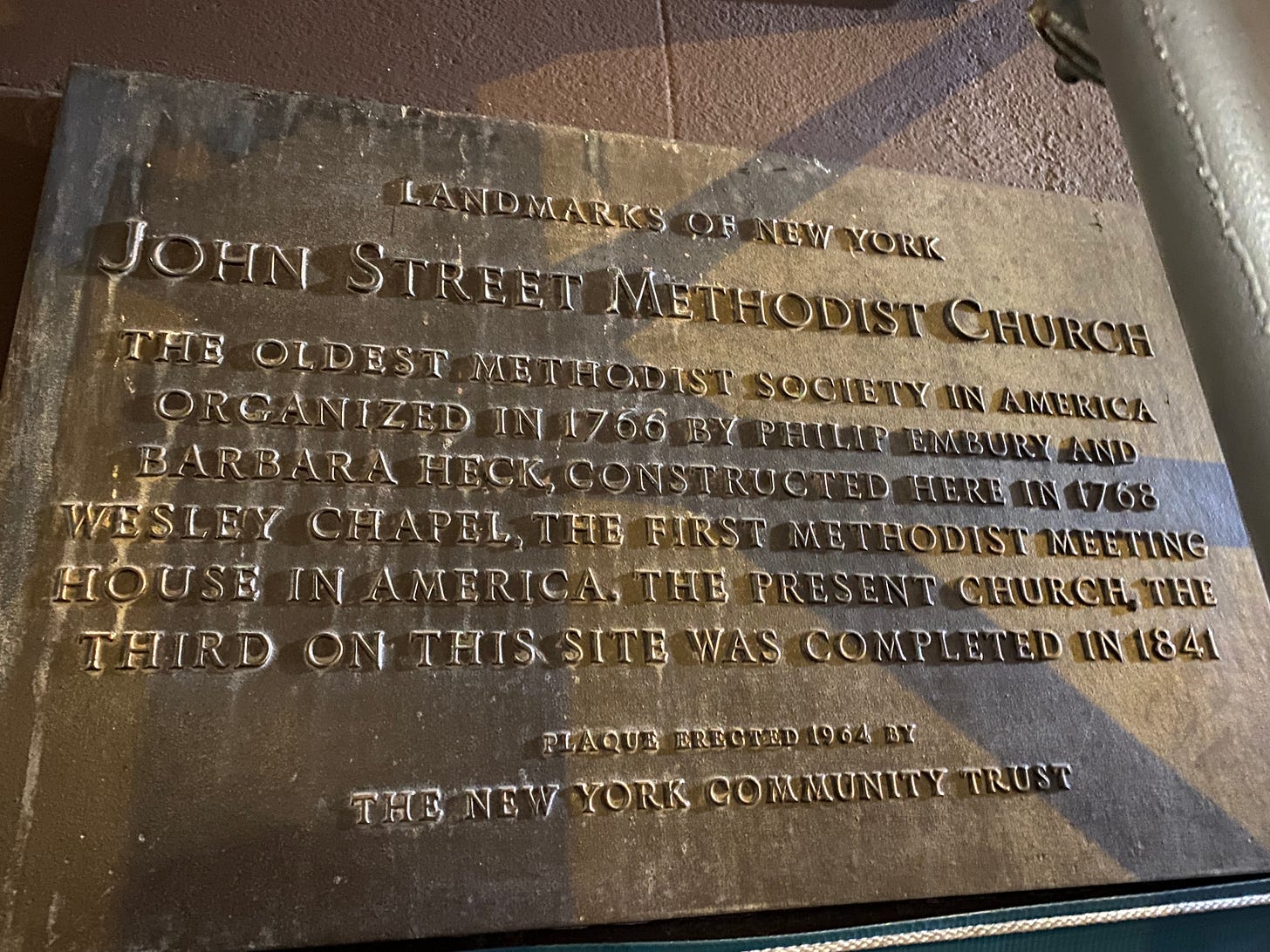

A few weeks ago, I traveled to New York City to visit friends in Manhattan, and they took me to the first Methodist Society in America (see picture below) established in 1768.

When Asbury arrived in Philadelphia in October this would have been one of a small handful of societies and preaching houses from New York to northern Maryland. There were only four missionaries on site in the colonies.

A few years after arriving, the Declaration of Independence was signed and the Revolutionary War had begun. While most missionaries began returning to England at the outbreak of the war, Asbury was one of only two Methodist preachers to remain.

This decision to go against the status quo was the first of many.

His faithfulness to stay steady during a difficult time and ride out the storm of war helped preserve the new work in the colonies. The word “maverick” is defined by dictionary.com as,

“an independent individual who does not go along with a group or party”.

Time and again, Asbury would make sacrifices that set him apart from the others.

He led a life of voluntary poverty, never married, and owned no more than he could carry on horseback. He rose at 4:00 am each morning to spend at least an hour in prayer, and preached more than 10,000 sermons in his lifetime.

He didn’t do it by going along with the crowd. He didn’t settle. He pressed forward when others encouraged him to quit. He went left, when others told him to go right.

He was a maverick leader with deep conviction.

In his book The Democratization of American Christianity, Nathan Hatch writes,

“Starting from scratch prior to the Revolution, Methodism in America grew at a rate that terrified other more established denominations. By 1820, Methodist membership numbered a quarter million; by 1830 it was twice that number.”1

What began as a fledgling group of societies erupted with over 500,000 participants over the course of his lifetime.

Asbury was indefatigable.

In one year he rode 3600 miles, performed 13 annual conferences, stationed 270 itinerants, and push himself to such exhaustion that by years end he wrote, “I am sometimes tempted to wish to die”.2

His sacrifice gave him the credibility to govern others the way he did and he expected nothing less from his traveling preachers. Indeed, they were the only members of the annual conferences allowed to vote.3

Asbury’s system simply did not allow for halfhearted participation and his bias was always toward the edges of the movement not the center.

If a preacher chose to settle down and locate in one area as a local preacher spending his time shepherding a group of classes or society, they forfeited the right to full membership in the fraternity of “mavericks” otherwise known as the Methodist Connection.

Profile of a Maverick

Most traveling preachers or “mavericks” were in their twenties or thirties and unmarried. Marriage was seen as a threat to the network as it became the leading reason itinerants would settle down as a local preacher.

The intense travel schedule and low pay made it difficult to provide for a wife and kids.

“Until 1800 full-time itinerants were only paid $64 per year. Most Congregational ministers made 7X that amount, had lifetime appointments, and the majority ministered their entire career in only one church.”

The life of a “maverick” consisted of traveling a two to four-week circuit on horseback that was often 200 to 400 miles in circumference. They would typically preach twenty-five to thirty preaching appointments per round in addition to checking in on the leaders of the numerous classes and societies on their circuit.4

The day-to-day activities would consist of preaching to the lost, forming and examining classes at each appointment, holding quarterly meetings at a centralized location on the circuit, and eventually hosting an annual camp meeting or revival.

They were radically innovative in reaching and organizing people and their meetings were often held in homes, court houses, schools, barns, or even the open woods.

In spite of the challenges, the attitude of most was exemplified by one itinerant,

“No one is worthy of the name of a traveling preacher that does not cheerfully go anywhere he can, for the general good of the entire movement. Better many individuals suffer, then the work at large should”5

It was not an easy life.

They ventured into unknown regions far from family and friends. They were ridiculed and threatened and the difficult pace of traveling and preaching created the inevitable risk of sickness, accident, and death.

This was the life of someone who went against the status quo of upward mobility, respectable ministry, and predictability.

The early American Methodist “mavericks” were cut from a different cloth than their established-church counterparts.

They were willing to be counter-cultural, to blaze new trails, and move toward the frontier. If the Congregational system was to settle down and find a nice place to preach, they would not.

Instead, they blazed new trails, challenged the status quo, and formed strong convictions in reaching the lost. They believed in the potential of revival to such a degree, they were willing to make radical sacrifices for the greater movement.

They were unconventional.

They were young.

They were idealistic.

They faced danger and even when they had setbacks, their perseverance was noteworthy.

Maverick Leadership in 2022

Which brings us to Top Gun.

In the opening scene of the 1986 hit movie Top Gun, US Naval Aviator Pete “Maverick” Mitchell and Nick “Goose” Bradshaw are seen flying a F-14 Tomcat high above the Indian Ocean and their aircraft carrier, the USS Enterprise. Maverick lives up to his name as his independent streak often puts himself and Goose in precarious and even dangerous situations.

Nonetheless, his excellent piloting skills land him a position in the elite training academy otherwise known as Top Gun. In one particularly memorable scene, Maverick and another pilot named Iceman are engaged in a heated locker room conversation after a day of training. Iceman looks at Maverick and Goose and the following dialogue ensues.

Iceman: “You two really are cowboys”.

Maverick: “What’s your problem, Kazanski?”

Iceman: “You’re everyone’s problem. That’s because every time you go up in the air, you’re unsafe. I don’t like you because you’re dangerous.”

Maverick: “That’s right! Iceman. I am dangerous.”

It’s a classic line.

The hit song played at the end of the movie talks about the danger zone and bellows, “the further on the edge the hotter the intensity”.

“Maverick leadership is about more than adventure. It’s also dangerous.”

Goose dies and Maverick must reassess his mission and calling.

On May 27th a new movie is being released called Top Gun: Maverick. It’s been thirty years and Maverick must now training a detachment of graduates for a special assignment. However, to move forward he must confront the ghosts of his past and his deepest fears.

It will culminate in a mission that demands the ultimate sacrifice from those who choose to fly it.

Being an early American Methodist maverick had little to do with rebellion or being wildly independent. Instead it was marked by sacrifice and a commitment to a cause. Not content with the status quo, they persevered for something greater than themselves.

There was a price to be paid and while the price was high, the results were legendary.

(edited from the full paper “Early American Methodist Mavericks”)

Hatch, N. (1989). Democratization of American Christianity. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, p.3.

Wigger, J. (2009). American saint: Francis Asbury and the Methodists. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, p. 229.

Hatch, p. 87

Wigger, J. (1998). Taking heaven by storm: Methodism and the rise of popular Christianity in America. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, p. 35.

Wigger, p. 215.